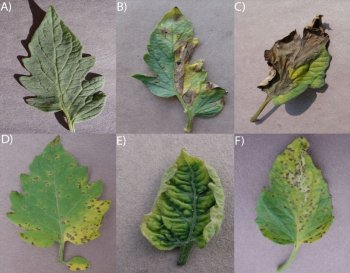

To address this problem, scientists from Penn State and EPFL, the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne, Switzerland, are releasing 50,000 open-access images of infected and healthy crops. These images will allow machine-learning experts to develop algorithms that automatically diagnose a crop disease. The tool then will be put into the hands of farmers -- in the form of a smartphone app.

"By providing all these images with open access, we are challenging the global community in two ways," said David Hughes, assistant professor of entomology and biology, Penn State. "We are encouraging the crop-health community to share their images of diseased plants, and we are encouraging the machine-learning community to help develop accurate algorithms."

The entire world depends on a stable food supply. Global population is predicted to reach 9 billion by 2050, and the need for food security is becoming increasingly urgent. Meanwhile, crop diseases continue to plague humanity, causing mass starvations. The challenge, then, is to grow enough food while ensuring that it is not lost to pests and diseases.

The Irish potato famine alone killed more than a million people in the 1840s when the water mold, Phytophthora infestans, caused a blight that decimated the country's crop. Today, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations estimates that crop diseases annually reduce potential yields by as much as 40 percent.

The idea behind releasing the open-source image database is to provide software developers with the "raw materials" to build machine-learning algorithms, according to Marcel Salathé, associate professor at EPFL and formerly a faculty member at Penn State. He explained that machine learning is a computational way of detecting patterns in a given data set to make inferences in another, similar data set. Fueled by breakthroughs in algorithm development, cheap computing and cheap storage of very large data sets, the results of machine learning have permeated our everyday digital experiences, from face-recognition in photos and videos, to recommender systems in online shops.

"The next step," Salathé said, "is to combine the enormous expertise in data science around the globe with our open-access data sets in the form of online competitions to develop the best algorithms to diagnose plant diseases. In the very near future, we'll launch the first online competition based on this growing data set that we make available today."

What Hughes and Salathé want to do is to apply these techniques developed by computer scientists to the problem of recognizing and diagnosing crop diseases. Algorithms with sufficient accuracy will be incorporated into smartphone apps, allowing farmers to snap pictures of their infected crops and get instant diagnosis and treatment advice.

For the two scientists, this is a natural evolution of their website, PlantVillage, possibly the world's largest free library of science-based knowledge on plant diseases. The still-growing site covers 154 types of crops and more than 1,800 diseases and now houses the new image database.

"In addition to being a library, PlantVillage is a network of experts who help people around the world find solutions to their problems," Salathé said. "Our goal is to let the smartphone do most of the diagnosis, so that human experts can focus on the unusual and difficult cases."

The smartphone app is the next progression in this evolution, utilizing the imaging capabilities and connectedness of smartphones to automate the recognition of plant diseases. "The beauty of the phone is that it penetrates society from community gardens in Brooklyn to smallholder farms in Burkina Faso," Hughes said.

With an expected 5 billion smartphones in the world by 2019, mobile apps have an enormous potential to transform how food is grown.

The bottleneck in the process is training algorithms to recognize diseased and healthy crops. Despite how affordable and accessible digital photography has become, finding enough publicly available images of crop diseases to train algorithms has been impossible until now.

Kelsee Baranowski, a member of the PlantVillage team at Penn State who has played a major role in creating the newly released images, emphasized the crucial role experimental research stations play in building the database of photographs. "Having access to field trials where plant scientists have experimentally infected crops is great because it allows us to get a sufficiently high number of images," she said.

"This is a truly exciting venture" said Hughes. "The Internet and mobile platforms have transformed many aspects of human civilization. Through these online competitions and crowdsourcing we want to transform the cornerstone of human societies -- how we grow food."

A paper authored by Hughes and Salathé describing the image database and machine-learning project was published Nov. 24 online in ArXiv.

Source: Penn State News

Classifieds

Classifieds